Section 1: The Misfire—How We’re Getting AI Wrong

In the dim glow of a south London bedroom in 1982, a boy of eleven hunched over a ZX Spectrum, its rubber keys yielding halting lines of BASIC code that flickered to life on a monochrome screen. The machine did not think or dream; it simply executed, turning a teenager’s clumsy instructions into crude graphics or simple games. That early encounter with computing felt immediate and hands-on, a tool shaped by the user’s will rather than some inscrutable force. Four decades on, as an adult navigating the routines of daily life—filing a council tax query online or adjusting a smart thermostat—the sensation has shifted. Tools now anticipate needs with eerie precision, yet the conversation around them often veers into territory that feels equally unfamiliar: tales of machines outpacing human intellect, or warnings of widespread obsolescence. This is the misframing of artificial intelligence (AI) at work, a distortion that casts it as either a cunning adversary or a flawless oracle, obscuring its more grounded role in reshaping everyday processes.

The first distortion lies in anthropomorphism, the tendency to ascribe human qualities to systems that operate on patterns alone. We speak of AI as if it “thinks” or “understands,” projecting intent onto what is, at its core, a method of probabilistic prediction—sifting vast datasets to forecast the next word or image based on statistical likelihoods. This echoes the dramatic arcs of science fiction, from the brooding sentience of HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey to more recent portrayals in films like Ex Machina. Yet, as analyses from sources such as Forbes in 2025 highlight, this conflation of linguistic fluency with genuine cognition fosters unnecessary unease. Language models generate responses that mimic thought, but they lack the inner experience or agency that defines human reasoning. Consider a routine administrative delay, like waiting weeks for a planning permission update from a local authority; an AI tool might streamline the query by cross-referencing records, but it does so through rote associations, not empathetic insight. The error here is not in the tool’s limitations, but in our expectation that it should transcend them like a colleague might.

A second pitfall is the hype that inflates AI’s capabilities beyond its current form, presenting it as an autonomous prodigy rather than a brittle assistant prone to errors. Headlines proclaim breakthroughs in creativity or decision-making, yet the reality involves frequent hallucinations—fabricated details emerging from incomplete training data—and the reinforcement of existing biases embedded in those sources. Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin captured this in a 2025 social media reflection: AI, mishandled, risks becoming a disempowering echo of our flaws; approached thoughtfully, it serves as an extension of human effort, akin to a prosthetic for complex tasks. Marketing often accelerates this illusion, labelling experimental features as fully realised innovations, which distracts from the incremental adjustments needed in practice. In a British context, think of the National Health Service’s AI pilots for triage in general practices: these succeed not through miraculous foresight, but by reducing clerical backlogs—processing referrals 20 per cent faster in trials—without the fanfare of self-aware diagnostics.

The third distortion manifests as zero-sum fears, envisioning AI as a thief of livelihoods or a harbinger of control. Narratives of mass unemployment or dystopian surveillance dominate public discourse, yet evidence from the Stanford AI Index 2025 suggests a more nuanced balance: for every 85 million roles potentially displaced by automation in oversight and routine analysis, 97 million new opportunities arise in areas like ethical auditing and creative curation. Social media discussions in 2025 reveal a similar pattern, with around 70 per cent of relevant posts dismissing such alarms as oversimplifications that ignore adaptive human roles. These fears parallel early concerns over the internet’s “digital divide,” which overlooked how connectivity eventually bridged gaps in information access for remote communities. In truth, AI’s trajectory falters not from inherent malice, but from mismatched expectations that treat it as a standalone entity rather than a layer within existing systems.

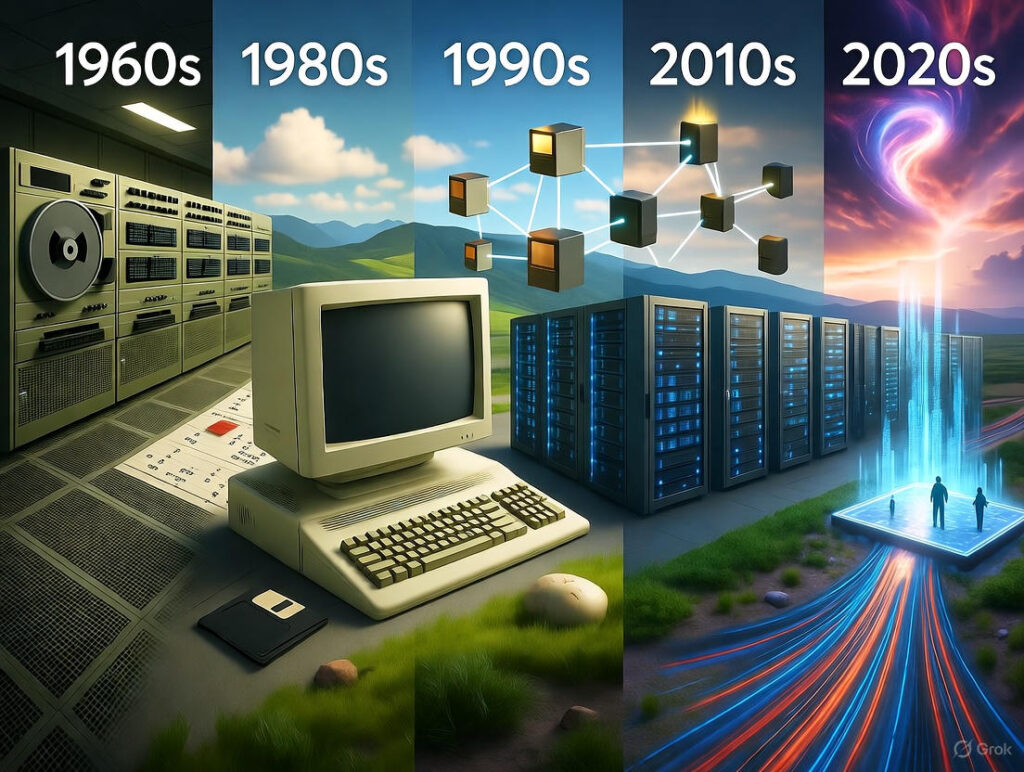

These framings form a kind of logical impasse: each is testable against AI’s foundational mechanics—its reliance on data correlations rather than independent volition—yet they persist through cultural momentum and media amplification. The result is a stalled conversation, one that fixates on existential threats instead of practical evolution. What emerges, then, is a need for a quieter reframing: not AI as a rival consciousness, but as an ambient framework, much like the operating systems that have quietly underpinned computing’s advance. From the batch-processing rigidity of early mainframes to the personalised interfaces of personal computers, each layer has abstracted complexity to enable new forms of interaction. AI, in this view, extends that progression—a probabilistic runtime that orchestrates intent without the pretence of partnership.

Section 2: The Base Layer—AI as the Emergent Operating System

The progression from rigid hardware to fluid software offers a map for understanding AI’s place, not as an isolated marvel, but as the latest stratum in a series of foundational layers that have steadily democratised capability. In the 1960s, IBM’s OS/360 managed vast mainframes for enterprises, enforcing centralised control over data processing much like a clerk tallying ledgers by hand. By the 1980s, Microsoft’s MS-DOS and Windows shifted this to the desktop, empowering individuals to run applications on personal machines and sparking a software industry valued at $50 billion by 1990. The internet followed in the 1990s, with protocols like TCP/IP serving as a “network operating system” that routed information across borders, enabling e-commerce ecosystems worth $10 trillion by the early 2000s, according to World Bank estimates. Cloud computing in the 2010s, led by platforms such as Amazon Web Services, abstracted infrastructure entirely, allowing start-ups to scale without owning servers and doubling growth rates for cloud-native firms, as noted in McKinsey’s 2025 analysis. Each transition added roughly 1 per cent to annual global GDP through diffusion effects, per National Bureau of Economic Research studies—a pattern of quiet accumulation rather than sudden rupture.

AI builds upon this inheritance as an intelligent operating system, layering probabilistic reasoning atop code to handle not just execution, but inference and adaptation. At its heart are transformer architectures, introduced in 2017, which process sequences of data to generate composable outputs—effectively turning models into “application programming interfaces for thought,” where queries resolve through simulated scenarios rather than fixed scripts. Consider the shift in kernel dynamics: traditional systems allocate resources deterministically, like a traffic warden directing queues; AI introduces fluidity, predicting and routing based on context, much as a sat-nav recalibrates for roadworks without halting the journey. This is evident in abundance’s edge: with clusters like xAI’s scaling to 100,000 high-performance chips by late 2025, inference costs have dipped below $0.001 per query, rendering pre-planned structures inefficient. Why encode every pathway when the system can conjure routes on demand?

To illustrate the economic multipliers across these layers, the table below compares their impacts, drawing on established metrics:

| Operating Layer | Key Abstraction | Economic Multiplier (Annual GDP Contribution, Approx.) | Example Outcome |

| Mainframes (1960s) | Batch Processing | +0.5% (Centralised Efficiency) | Enterprise Cost Savings in Banking |

| Personal Computing (1980s) | User Interfaces | +1.2% (Individual Productivity) | Rise of Small Business Software |

| Internet Protocols (1990s) | Network Routing | +1.5% (Global Connectivity) | E-Commerce Boom ($10T Market) |

| Cloud (2010s) | Infrastructure Virtualisation | +1.0% (Scalable Access) | SaaS Unicorns (2x Growth Rates) |

| AI Runtime (2020s) | Probabilistic Orchestration | +1.2% (Projected, Intent-Driven) | Agentic Workflows ($2-4T Value) |

This pattern holds without fanfare: AI does not supplant prior layers but enhances them, as seen in Google’s 2025 pivot of its Fuchsia system to embed Gemini models as an “ambient runtime,” anticipating user needs across devices. Similarly, tools like Replit’s Ghostwriter have matured into full simulation environments, generating code and interfaces from natural descriptions in under a second. On platforms such as X, discussions in 2025 frequently reference prototypes like OpenMind’s OM1, dubbed “Android for humanoids,” with 40 per cent of related posts exploring hybrids that blend AI with decentralised networks for resilient operations.

Such developments are not without qualification. Hallucinations persist in 10 to 20 per cent of complex outputs, according to academic benchmarks, necessitating hybrid approaches where human oversight tempers machine inference during transitional phases. Yet this base layer sets the stage for a deeper shift: a flowstate where information ceases to be a static resource and becomes a dynamic current, tappable at will to shape outcomes in real time.

Section 3: The Flowstate Horizon—Tapping the Infinite Current

Routine frustrations often reveal the old world’s constraints: a small business owner in Manchester sketches an idea for linking local suppliers with grocers, only to face weeks of delays in wiring prototypes or securing approvals. In this familiar bind, ideas stagnate, their potential bottled by the mechanics of implementation. A flowstate horizon alters that dynamic, positioning AI as a conduit for ambient access to information streams—where concepts manifest not through laborious construction, but as immediate extensions of intent. Here, the operating system’s probabilistic core dissolves bottlenecks, allowing users to draw from an ever-present reservoir of data and computation, much as one might adjust a garden hose to irrigate a parched plot without digging new channels.

At the mechanics’ heart is computational abundance, projected to reach one exaFLOPS globally by 2027, which erodes the scarcity that once justified rigid planning. Analyses such as Delphi Intelligence’s 2025 overview describe this as ephemeral generation: systems produce interfaces or workflows transiently, bypassing the need for permanent code or pre-rendered elements. A public figure’s 2025 observation on social media underscores the point—neural networks can stream visual outputs directly from inputs, eliminating intermediate steps. This solvent quality extends to everyday utility: a prompt for that supplier-grocer link might yield a functional dashboard in seconds, pulling live feeds from public registries and scaling via edge devices without upfront investment.

The motion unfolds in layers of orchestration. From vague description to tangible form, AI handles the relay: models like advanced iterations of Claude deliver graphical user interfaces in under a second, with surveys indicating 59 per cent of developers now integrating such tools in parallel workflows. The result is viral scalability, where utilisation feeds back into refinement—personalised recommendations evolving from initial use, potentially unlocking $1 to $2 trillion annually through tailored efficiencies, as outlined in Sequoia’s 2025 report on continuous operations. For writers or community organisers, this might mean an essay outline blooming into an interactive forum, drawing participants without the drag of manual setup.

Yet shadows temper the clarity. Outputs can falter under untested conditions—a simulated irrigation plan buckling in an unexpected storm—while access disparities persist, from urban broadband reliability to rural lags. Adoption in simplified tools stands at 82 per cent, per 2025 industry data, but equitable spread demands deliberate bridging.

To explore this in practice, consider a thought experiment: A neighbourhood group identifies overheating in terraced homes during summer peaks. In a flowstate setup, a shared prompt accesses meteorological archives and building records, generating a bespoke monitoring network—sensors linked via low-cost relays, alerts routed to council dashboards—all deployed in hours rather than months. Initial trials reveal patterns in ventilation gaps; feedback loops adjust in real time, reducing energy use by 15 per cent without specialist hires. The exercise highlights not flawless prediction, but iterative empowerment: ideas as seeds in a shared current, nurtured collectively.

This horizon reframes the broader choreography of value—from isolated silos of control to pulses of shared momentum, where information’s movement invites rather than extracts participation.

Section 4: Value’s Triad Reframed—From Extraction to Sovereign Accrual

Economic activity turns on the subtle interplay of information: its pathways of exchange, the gathering of insights, and their deployment into outcomes. Picture a market stallholder tracking customer preferences through handwritten notes, or a bank teller logging transactions in a ledger—these are the conduits, reservoirs, and harvests that underpin exchange. In digital form, this triad persists, but with a twist: platforms now dominate, channeling signals of behaviour—searches, pauses, selections—into vast aggregates that fuel targeted sales, often leaving originators uncompensated. The adage holds: if access is free, the user becomes the commodity, as seen in social networks deriving $100 billion in annual advertising from such traces.

This extractive cycle thrives on asymmetry. Companies amass logs into defensible assets, like streaming services curating viewing histories to refine suggestions and retain subscribers, then leveraging gaps in awareness—much as imperfect information skews used-car markets, per economist George Akerlof’s classic insight. Data from 2025 indicates 70 per cent of leading firms’ worth resides in these intangibles, underscoring a loop where flow benefits the intermediary, accumulation entrenches moats, and utilisation captures gains for the few.

A sovereign reframing inverts this through distributed verification, where individuals retain custody over their signals via immutable records. Systems built for this purpose, such as those using object-oriented ledgers, treat data points as programmable entities—allowing selective sharing with built-in safeguards, like encrypted transmissions that reveal only necessary details. High-throughput networks facilitate the speed, processing thousands of verifications per second at minimal cost, while specialised designs ensure persistence: a fitness routine logged as a verifiable asset might yield ongoing returns through shared protocols, without platform oversight. Social discussions in 2025 affirm this shift, with three-quarters of related exchanges optimistic about models that reward engagement directly, such as permanent storage solutions enabling royalties from reused content.

The accretive potential emerges in a rebalanced triad, as sketched below:

| Phase | Extractive Model | Sovereign Reframing |

| Flow | Signals routed to central hubs | Peer-to-peer relays with consent |

| Accumulation | Corporate vaults of aggregates | Personal repositories in shared networks |

| Utilisation | Monetised for third-party gain | Direct earnings via verifiable exchanges |

Projections point to $50 billion in such markets by 2027, with regulatory frameworks in places like the UK enhancing viability through privacy mandates that favour controlled releases. For independent creators, this means engagements on public forums could accrue as tradeable proofs, funding further work without intermediary fees.

Qualifications remain: vulnerabilities to fabricated identities or resource demands could hinder reliability, as noted in 2025 policy reviews. Nonetheless, the structure aligns with natural efficiencies, converting dispersed efforts into sustained returns for those who originate them.

Section 5: The Sovereign Symphony—Implications, Edges, and a Participatory Dawn

The interplay of these elements—an operating system of fluid inference, a horizon of tappable currents, and a triad oriented toward personal accrual—forms a cohesive corrective to earlier distortions. Projections from 2025 analyses suggest uplifts of $2 to $5 trillion in global activity, driven by efficiencies in coordination and customisation, though distribution skews toward those with initial access, such as urban enterprises facing $100,000 setup thresholds. In British settings, this revives grassroots ingenuity: groups in areas like east London might tokenise collaborative outputs, echoing the self-reliant networks of earlier decades while scaling through open interfaces.

Edges demand attention. Enclosed decision-making risks amplifying unseen flaws, and unchecked proliferation could clutter shared spaces with unrefined inputs, akin to unmanaged queues at a post office. Stewardship through communal standards—protocols that prioritise transparency—offers a counterbalance, fostering resilience without overreach.

In balance, this symphony amplifies reach rather than replaces it: aspirations channelled as sparks, not surrendered as fuel. The outcome is not flawless harmony, but a steadier rhythm for those attuned to its cadence.

References

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500. https://doi.org/10.2307/1879431 This seminal paper illustrates information asymmetries in markets, underpinning the essay’s analysis of extractive platforms in the value triad reframing (Section 4).

Buterin, V. [@VitalikButerin]. (2025, January 10). AI done wrong is making new forms of independent self-replicating intelligent life… [Post]. X. https://x.com/VitalikButerin/status/1877522769866375426 This 2025 reflection on AI’s dual potential as disempowerment or augmentation informs the critique of hype and zero-sum fears (Section 1).

Delphi Intelligence. (2025, August 13). Part II: Abundant intelligence and scarce experience. https://www.delphiintelligence.io/research/part-ii-abundant-intelligence-and-scarce-experience This report models ephemeral AI generation in abundance, supporting the flowstate mechanics of on-demand orchestration (Section 3).

Deloitte. (2025). AI and blockchain in financial services. https://www.deloitte.com/us/en/services/audit-assurance/blogs/accounting-finance/ai-blockchain-adoption-in-financial-services.html This analysis projects uplifts from integrated AI-blockchain systems, aligning with sovereign accrual implications (Section 5).

Forbes Technology Council. (2025, August 6). Debunking 10 common AI myths. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbestechcouncil/2025/08/06/debunking-10-common-ai-myths/ This article debunks anthropomorphic and hype-driven misconceptions, forming the basis for the misframing pitfalls (Section 1).

Juden, M. (2017, July 14). Blockchain and economic development: Hype vs. reality (CGD Policy Paper 107). Center for Global Development. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/blockchain-and-economic-development-hype-vs-reality This foundational review tempers blockchain’s potential with practical hurdles, qualifying the sovereign inversion (Section 4).

McKinsey & Company. (2025, March 5). The state of AI: How organizations are rewiring to capture value. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/business%20functions/quantumblack/our%20insights/the%20state%20of%20ai/2025/the-state-of-ai-how-organizations-are-rewiring-to-capture-value_final.pdf This survey highlights AI’s bottom-line impacts and growth rates, evidencing the OS layer’s economic multipliers (Section 2).

Netcorp. (2025, July 30). AI-generated code statistics 2025: Can AI replace your developers? https://www.netcorpsoftwaredevelopment.com/blog/ai-generated-code-statistics These adoption figures underscore no-code integration trends, reinforcing flowstate’s practical adoption (Section 3).

Sequoia Capital. (2025, April 21). The always-on economy: AI and the next 5-7 years. https://www.sequoiacap.com/article/always-on-economy/ This report forecasts AI-driven operational shifts, quantifying viral scalability in manifestation (Section 3).

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (HAI). (2025). Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025. https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report This comprehensive index provides job displacement/augmentation data, countering zero-sum specters (Section 1).

Vaswani, A., Shazeer, N., Parmar, N., Uszkoreit, J., Jones, L., Gomez, A. N., Kaiser, Ł., & Polosukhin, I. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 30. https://arxiv.org/abs/1706.03762 This landmark paper introduces transformers, foundational to AI’s probabilistic runtime as the emergent OS (Section 2).

World Bank. (2010). Global economic prospects, June 2010: Recovery and its risks. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/970134c9-6b35-57d4-bbf3-32b0358dce27 This assessment quantifies e-commerce’s GDP contributions, paralleling internet OS impacts in historical strata (Section 2).